From Kangro’s Ford buses to modern public transport

Regular bus transport can be said to have started in Tallinn on 22 May 1922, when the city government granted permission to the architect and entrepreneur Fromhold Kangro to operate five bus routes in Tallinn and its vicinity: Vene turg (current Viru Square) – Tartu maantee, Vabaduse plats – Seevald, Vene turg – Kalamaja, Vene turg – Pirita, and Vene turg – Kose.

On 7 May 1922, the buses of the enterprise Fromhold Kangro ja Ko started roaming on Tartu maantee between Vene turg and the edge of Lasnamäe. Passengers were served by five somewhat old Daimler double-decker buses, which had the upper deck removed, as the city government did not believe that the pavement on Tartu maantee could withstand such heavy loads. Another reason was that the rickety buses would not have been up to carrying a full load of passengers anyway. The departure interval was 10 minutes and the fare was 15 marks. Soon after, the rest of the routes were also launched, taking passengers to Seevald, Kalamaja, Pirita, and Kose. However, by 1926, F. Kangro’s debts to the Credit Bank became so great that he was forced to transfer the company’s rights to the bank.

On 26 January 1926, the private limited company Mootor, with the Credit Bank as the main shareholder, started business using the resources acquired from F. Kangro: 23 buses, a garage at Tartu maantee 53b, and Kangro’s former employees. Over the next few years, Kangro’s Fords were replaced by new Graham, Reo, and Federal buses. The route network expanded across Harju County, with the longest routes transporting passengers to Pärnu and Kuressaare. Mootor’s business operations met with economic success and the city government monitored it for years, as they believed that Mootor was more interested in developing profitable routes.

In 1928–1929, the city entered into negotiations to buy up Mootor’s business with the intent of running it itself. However, the transaction was called off, because the city government found the price to be too high. In December 1937, the city government finally launched its own buses on a new route running from the city centre to Kopli, and also managed to take over a few routes from Mootor until the summer of 1940, running ten one-year-old Büssing motorbuses acquired from Mootor and three older buses. Mootor’s buses were all painted red, while the buses operated under the tram fleet by the city government were blue. Before the start of 1940, construction also began on a new garage and workshop for the city’s tram depot that was to accommodate roughly one hundred buses.

Following the coup in June 1940, the new authorities merged the two companies. The Tallinn Automobile Holding Mootor had over 130 buses, most of them modern, no more than three years old Büssing NAG, Volvo, and Scania-Vabis buses. The Soviets brought seven brand new long-nosed ZIS-16 buses to Tallinn.

Sadly, this vast modern bus fleet was almost completely wiped out in the first three months of the war. A number of buses were commandeered to evacuate the population or transport mobilised men across the eastern border to Russia, and never returned. Some, carrying battalions, were left on the battlefield. The final blow came in late August 1941, when the Germans opened fire from Lasnamäe on a caravan of ships that was currently being unloaded in port. On 27 August, fire was concentrated on the cruiser Kirov, which was parked right next to Mootor’s garages (in the area of the current Tallinn City Hall). The garages were blown to smithereens, with 23 buses destroyed in the resulting fire and buried under rubble.

After the smoke of battle had dissipated in Tallinn, around 30 surviving buses were counted. These fitted neatly into the tram depot on Pärnu maantee. On 1 November 1941, Mootor’s remaining property and personnel were transferred to the company Linna Tramm ja Autobused. The 19 city buses were all painted blue and outfitted with a wood-gas heating system. They were mainly used to take passengers to and from Merivälja, as Nõmme was also accessible by electric train. In these gas-heated buses, there was a large oven in the middle of the passenger compartment, where one could easily prepare smoked meat. The drivers and conductors took advantage of it for themselves as well as their relatives and acquaintances – a single batch could be prepared in around the same time it took to make three trips to Merivälja. In the autumn of 1941, intercity routes were taken over by the postal service provider Kraftpost, who acquired eight of the larger buses of Mootor. These, too, fitted into the tram depot, but had to use a separate entrance.

In 1944, the ongoing war brought bus traffic to a halt and inflicted new losses. After the war, only 12 of the buses run by Kraftpost and Linna Tramm remained operational. These entered the possession of the newly established enterprise Tallinna Trammi ja Autobuse Trust. On 23 October 1944, an article in the newspaper Õhtuleht promised that the Nõmme route would be reopened in two days, the Merivälja route after the Pirita bridge would be repaired, and inner city routes in the near future, when ‘the buses taken to Leningrad away from the war’ in 1941 would return. None of these buses ever returned, although eight ZIS bus wrecks belonging to the navy were delivered to the tram depot. Two of them were eventually even restored to working order.

Intercity routes came to be operated by the Tallinn Automobile Holding No. 1, which declared the opening of routes to Viljandi, Loksa, and Kose in November 1944. These were initially served by open-top trucks, which were later fitted with closed compartments. Harju County Automobile Holding No. 5, too, entered the bus transport business. At first, they had nothing but a square in Ülemiste – the very same square where the entire enterprise of the Tallinn Bus Fleet (Tallinna Autobussipark) was developed until 1967, then left to the Ülemiste branch that operated intercity routes, which split off in 1990 under the name Mootor and became embroiled in a privatisation debacle, today the site of the Ülemiste shopping centre.

Previously, the Germans had planned to build an automobile depot on the site, having even brought in a portable aircraft hangar from Põllküla. Trucks left behind from the war began to be collected on the square – first from nearby in Ülemiste, then from Seevald, and in the summer of 1945 from further afield: from Courland and Liepaja. Eventually, a joint delegation of the Tram Trust and the 5th Automobile Holding drove their truck all the way to Berlin and, on the way back, collected a total of 23 vehicles from among the spoils of war seized in Königsberg and Tilsit. The cars and buses of the 5th Automobile Holding were refurbished on Laulupeo Street, in the garage of the former transport company of Eduard Poola, where a large part of the work was done by German prisoners of war.

In the end, however, the 5th Automobile Holding only managed to pull together three buses. The Ministry of Road Transport and Roads thought that it would be wiser to hand all bus operations over to the 1st Automobile Holding. Thus, on the evening of 3 December 1945, the buses of the 5th Automobile Holding were driven to the petrol station on Estonia puiestee, which was located right next to the offices of the 1st Automobile Holding at Tatari 1. The weather, however, turned very cold that night, and it got even colder on the following day, which led to the men of the 1st Automobile Holding failing to get the buses running. The Ministry then concluded that the 1st Automobile Holding was not up to scratch, and reversed the decision: the 5th Automobile Holding was given 11 additional buses and the task of starting bus services on the Merivälja, Kose, Loksa, Pärnu, and Riguldi routes on 8 December 1945. They were successful, and thus the 5th Automobile Holding was born as a motorbus operator – despite the fact that even as late as 1 July 1946, the holding owned 106 trucks and 20 buses, of which only five were operational, 13 were under repair, and two were wrecks.

In spring 1947, a decision was made to have the 5th Automobile Holding take over the bus fleet of the Tram Trust, which was by no means in better condition. On the day of the takeover, 11 April 1947, only one of the Tram Trust’s 14 buses was fit to drive. The rest were being overhauled or awaiting suitable tyres. Eventually, nevertheless, they were all successfully put into service.

On 31 January 1948, Automobile Holding No. 15 was established in Nõmme, which acquired all of the trucks of the 5th Holding, thereby ending the freight transport operations of the latter. On 1 August 1949, the 5th Automobile Holding was renamed the Tallinn Bus Fleet (Tallinna Autobussipark). The time of confusion was over, the bus fleet began to expand steadily, and the route network grew rapidly.

In the spring of 1948, the first four ZIS-154 diesel-electric buses arrived from Moscow, manufactured by the Stalin Plant as a modified version of one of American manufacturer GMC’s bus models. Drivers christened them ‘Lightning Bolts’ in reference to the unprecedented speed of the buses. The Lightning Bolts were not easy to operate – as illustrated by the fact that, in addition to 30 brand new buses, Tallinn received the same amount of used buses from Leningrad, Frunze, and Ashgabat. After a year of trialling, Tartu, too, sent its only two Lightning Bolts to Tallinn.

In 1950, the ZIS-154 was discontinued in favour of the ZIS-155. This was a petrol-powered model that looked somewhat compact compared to the Lightning Bolts, earning it the nickname ‘Kiddo’. By the end of 1955, almost the entire bus fleet consisted of Kiddos and Lightning Bolts. Thereafter, however, things got more interesting, as new types of buses started arriving every year. First there was the ZIS-127, launched on intercity routes in the spring of 1956. With its riveted body and high seats, the ZIS-127 resembled an airplane; its speed of up to 115 km/h was unparallelled at the time. These ‘Jets’, as they came to be called, were also exceptionally durable: the last two were decommissioned in 1973 after they had travelled 2 million kilometres.

1956 also saw the introduction of the first Ikarus buses to the fleet. These were the cigar-shaped Ikarus-55s, which featured skylights and served passengers on Pärnu, Viljandi, Rakvere, and other intercity routes. ‘Jet’ speed was not an option with these buses, as the body would sway wildly at high velocities due to ineffectual shock absorbers. As these Ikarus buses were primarily designed for carrying tourists in cities, it was no wonder that they did not last long on our highways. The last Ikarus-55 did, however, manage to grind out one million kilometres, after which it was driven back to Budapest in 1966, where it was put on display at the factory’s museum.

The first Ikarus-66 to serve our city routes was brought to Tallinn straight from an exhibition in Moscow in March 1957. Its body was similar to that of the Ikarus-55, but had three doors. Over time, 47 more such red city buses, except without skylights, were added to the fleet. Throughout the 1960s, they primarily operated on the Pääsküla and Merivälja routes.

In 1957, a number of smaller, Ikarus-60 buses – which the drivers called ‘Tractors’, and which really did sound like tractors – were also introduced. They were originally based at the Rocca al Mare dispatch centre, from where buses were dispatched to Mähe, Pelguranna, Klooga, and Keila-Joa in the late 1950s. An improved version of these ‘Tractors’ – the Ikarus-620 – began arriving from the end of 1963 and became a truly monumental bus model with the opening of the Mustamäe routes. In May 1965, as many as 60 of them arrived – an unprecedented reinforcement of Tallinn’s bus fleet. In October 1967, when city buses were relocated from Ülemiste to the new depot on Kadaka Road, the fleet already contained a total of 450 buses.

In April 1967, the first three white, articulated Ikarus-180 buses arrived in Tallinn, followed by regular, white, three-door Ikarus-556 buses of the same series in spring 1968. The era of the white Ikarus buses eventually came to an end in Tallinn in late 1983, when they were replaced by yellow Ikarus buses. (These, in turn, would reign until the summer of 1992, when the first set of old Volvo buses was brought in from Finland.) In October 1973, 22 new Ikarus-260 buses were put into service together, followed by a number of articulated Ikarus-280s in 1975. Ikarus buses became history in Tallinn in February 2003, when the last of them was formally retired on Freedom Square.

On 1 January 1985, the Tallinn Bus Fleet was reformed into the Tallinn Bus Company (Tallinna Autobussikoondis – TAK), headquartered in Mustamäe (at Kadaka tee 62a, which served as the base of operations of city routes), with a branch in Ülemiste (at Suur-Sõjamäe 2, responsible for operating intercity and suburban routes) and another branch in Lasnamäe (at Leningradi mnt 73, which mainly operated district and shorter-distance routes). On 1 January 1990, the Ülemiste branch split off from TAK and adopted the name AS Mootor. On 1 January 1992, TAK was reorganised into a state-owned public limited company and renamed RAS Tallinna Autobussikoondis. On 9 September 1993, ownership of TAK was transferred from the state to the City of Tallinn, and the city council decided that the enterprise would operate as a public limited company.

During the economically and politically difficult times of the early 1990s, the fleet was supplemented with used Volvo and Scania buses, until, in 1995, a bus factory established in Tartu started domestic production of city buses again.

New buses and cleaner city air

In 1995, the Tartu-based company Baltscan AS started domestic production of city buses based on Scania’s designs. The first Scania L113CLB buses manufactured by Baltscan AS for Tallinn were the only new vehicles purchased in 1990s that conformed to the Euro 1 emission standard. As environmental protection began to gain increasing attention as a modern issue, these vehicles did not prove very popular, and future Scania buses gradually started to improve in terms of their environmental performance. Both the Scania Hess L94UB and the Scania Hess L94 UB City, as well as the Scania bus train (which was not kept in service for long because of how cumbersome it was) complied with Euro 2 standards.

Unfortunately, the domestic manufacturer Baltscan AS soon went out of business due to tough competition, and the buses acquired since the start of the new century have come from foreign European manufacturers. Today, Tallinn’s streets are dominated by Scania and MAN buses conforming to the Euro 5 and Euro 6 emission standards.

Tallinna Linnatranspordi AS – towards a new standard of quality

In July 2012, the Tallinn Bus Company and the Tallinn Tram and Trolleybus Company were merged. The new, merged company – Tallinna Linnatranspordi AS – which was tasked with organising bus, tram, and trolleybus traffic, remained under the ownership of the City of Tallinn. In the new, integrated public transport company, bus transport has maintained its leading position both in terms of passenger traffic volumes and the number of routes.

The company’s development has gained particular momentum in recent years. The year 2019 was a turning point for the company, yielding the greatest increase in the number of passengers in its history thanks to innovations in management.

Until 2019, TLT operated 90% of Tallinn’s city routes for public transport. After the private company that previously operated the remaining 10% of the routes withdrew from their contract in February 2019 year, TLT became responsible for the management of 100% of all bus services provided to Tallinners. Thereafter, the 62 routes that TLT had at the start of the year became 75. The increased capacity is illustrated by the fact that, during peak hours, 440 of TLT’s 530 buses are out on the streets.

Headed for the future

TLT has created a long-term dynamic development strategy, under which 70% of the existing bus fleet is to be replaced with natural gas-powered buses in the coming years. An agreement is also in place for the construction of two new natural-gas refuelling stations on Kadaka tee and Peterburi tee. Once all 350 of the biomethane-powered buses are in service, CO2 emissions in the city should fall by approximately 25,000 tonnes per year, which is roughly equal to the average annual emissions of 7,000 passenger cars with internal combustion engines. At the same time, the dependence of Tallinn’s public transport system on diesel fuel will decrease by approximately nine million litres per year.

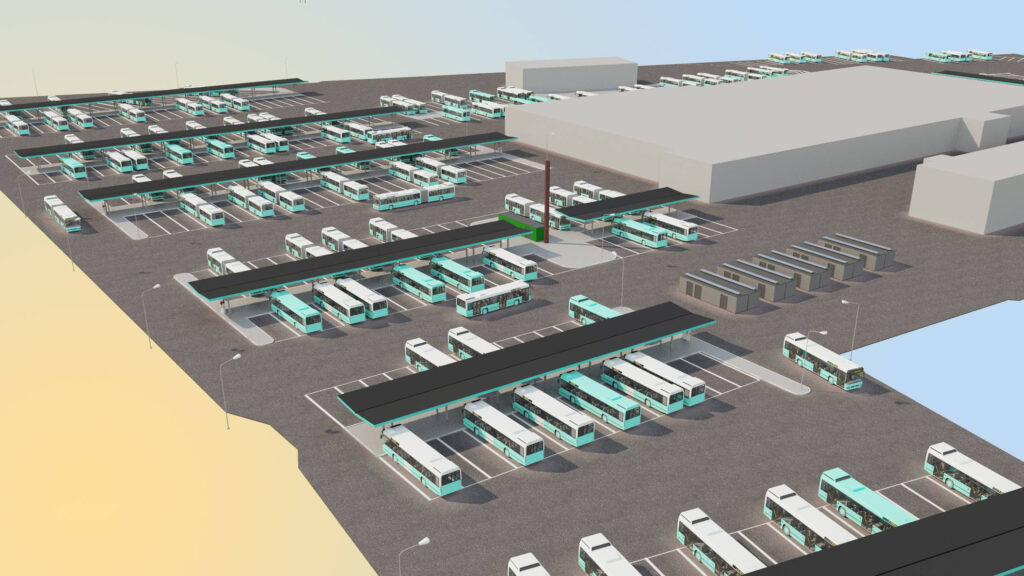

TLT’s management, however, is looking even further into the future. The rapid development of electric bus technology is set to create the conditions for switching the entire bus fleet over to electric buses by 2035 at the latest. Work is underway to make this major innovation a reality, and TLT is hoping to bring a number of demonstration buses to Tallinn for testing in the near future. This should enable a route served solely by electric vehicles to be launched as a pilot project.